- The Kodokan Bōjutsu Department – Staff Fighting in the Kodokan Institute -

One of the lesser-known aspects of the pre–Occupation Kodokan Institute was its instruction of jōjutsu (staff technique) and the Kodokan bōjutsu bu (Kodokan Staff Technique Department).

Tokyo Metropolitan Police guard the National Diet Building, Japan’s Parliament.

The righthand policeman holds a white oak jō,

while the lefthand policeman carries an extendable / collapsible keibō police baton.

Knife-proof vests, radios, and revolvers round out their uniforms.

In issues of Judo magazine in 1936 and 1937, the Heki Ryusuke (EN1), Kanō mentioned was an “instructor with the Kodokan Bōjutsu Kenkyū Bu” (bō technique research division).

He wrote a series of essays on Kodokan bōjutsu published every two months or so, beginning in March 1936 with the essay Bōjutsu no Shugyō Hōhō (“Methods of Intense Study of Bō Techniques”). Essentially that series introduces Kodokan bōjutsu courtesies, then solo techniques and paired kata; overall

it looks very similar to the modern SMR jōdō seitei kata standard forms, which can be seen in the Shimizu sensei video above.

The jō staff is a common weapon in many Japanese ryūha martial art schools, and ubiquitously wielded by Japanese riot police and police guarding police stations or other facilities, in uniform or in plain clothes.

Staffs come in a near infinite variety of lengths and thicknesses with a bewildering number of names, but in the past several decades their various names have become standardized through the popularity of Shintō Musō ryū jōdō (literally “The Way of the Gods-Dream Inspired School Staff Way”, abbreviated SMR by its aficionados.) There are some vague conventions that can be proposed regarding the terms. Here is a list for casual reference, which should certainly not be considered authoritative.

• Tsue, sutekki, or tanjō – in the early Meiji era, the term tsue came to be used for a cane, a ステッキ sutekki was a “walking stick”, while tanjō means “short jō”, usually around 1 meter / 39 inches in length. The near ubiquitous Victorian gentleman’s walking stick was adopted by many Japanese, particularly former samurai recently deprived of their traditional right to carry the daishō two-sword set. In those times of political and criminal violence, the legal-to-carry cane became a useful weapon for self-defense, and not infrequently used to conceal highly illegal sword cane blades. Minister of Education Mori Arinori’s assassin, Kanō’s jūdō student Nishino Buntarō, was nearly decapitated by Mori’s bodyguard using an illegal sword cane. (The former samurai bodyguard was tried for the murder of Nishino but exonerated.)

Kanō was almost certainly aware of the use of canes in martial arts self-defense in the later 1800s. The famous swordsman and ultranationalist Genyōsha member Uchida Ryōgorō developed an entire series of tsue versus sword techniques eventually called Uchida ryū tanjōjutsu using a 90-centimeter-long straight stick; supposedly he was set upon by two political opponents armed with illegal swords and he barely survived and developed the techniques to defend himself from such an attack. Years later his art was absorbed into the SMR jōdō curriculum and is still taught today to advanced students.

• Jō – an alternate reading for 杖 tsue, meaning stick or staff. Because of the prevalence of SMR jōdō, the definition used by multiple SMR jōdō associations describe a standard 127 centimeter / 50-inch round staff, traditionally made of Japanese white oak. The traditional Japanese length is 4 shaku 2 sun 1 bu (127 cm / 50 inch) with an 8 bu (24 mm) round diameter. Some schools use thicker jō of the same length.

SMR jōdō associations make allowances for shorter practitioners to shorten their jō to accommodate the full-length techniques in the kata repertoire, but there are no longer jō for taller practitioners. In some classic jō schools, the proper length is measured from the floor to the armpit of each individual practitioner, while in other schools jō are as long as 180 centimeters or more.

(Just to confuse things further, the staff used in the modern Kodokan Goshin Jutsu “Self Defense Techniques” series compiled in the 1950s is 1 meter / 39 inches long but is called a jō by jūdōka.)

• Bō – while less specific, this is often taken to mean a roku shaku bō, a 6 shaku or 182 centimeter / 6 foot 1-inch-long staff or cudgel. In modern days these are usually round, but may be hexagonal, which focuses the force of strikes into a smaller, sharper angle. Some of the larger bō and other staffs may be bound with shrink-fit iron rings to strengthen the wooden shafts and add mass for more destructive blows.

The legendary origin tales of bō schools sometimes entail some warrior’s losing the blade of his yari spear or naginata halberd in battle and having to fight with just the remaining wooden staff.

The primary introduction of SMR jōdō to Tokyo was by Fukuoka martial artist Shimizu Takaji 清水隆次 (1896–1978). Shimizu sensei was a senior Shintō Musō Ryū jōdō instructor, closely associated with the Genyōsha ultranationalist group and its dōjō, the Genbukan, where several koryū bujutsu ancient martial arts, including jūjutsu and jōjutsu, and, later, jūdō were and are still taught.

During the long Tokugawa era, the city of Fukuoka was the crown jewel of the Kuroda han feudal domain / fiefdom. While almost all han had a range of martial arts taught to its young samurai as part of their education as professional warriors, many of those schools were common across Japan and there was substantial cross training and exchanges between the different sites of the same schools, in the dōjō of Edo. But in some instances, the han would designate a particular martial arts school as its 御留流 otome ryū, a martial art designated for the sole use of the han that was never to be shown to outsiders. Normally those designated as otome ryū were kenjutsu sword arts, as a surprise, proprietary, novel technique could win a desperate battle against a more conventionally trained swordsman opponent, but according to the lore imparted (without evidence, it appears) by Shimizu sensei and other Shintō Musō ryū instructors since, uniquely the Fukuda han designated Shintō Musō ryū jōjutsu as an otome ryū. So, while many koryū bujutsu ancient martial arts included jō or bō techniques, there is no other known example of a jō school being so designated. (It is beyond the scope of this essay to explore the claim, but it is fun to convey the unique tale.)

Shimizu sensei studied other arts but focused on SMR jō and its associated minor arts: kusarigama sickle and weight on chain or rope, juttejutsu small cudgel, and hojōjutsu rope binding. Beyond the basic one-man drills, the paired SMR kata pits a jō armed practitioner defending against a series of complex attacks from an opponent armed with a sword. The longer jō allows a skilled user to check or attack the swordsman at will, using its longer reach to block the sword (or even to bend or break inferior blades), to inflict precise blows to fracture wrist, ribs or collarbones, to thrust to blind the eyes, to stun or kill with deadly blows to the temple, or, in the specialty of the school, exert hard thrusts and checks to the solar plexus to create a temporary paralysis of the attacking swordsman’s diaphragm and thus render him unable to breathe.

Shimizu sensei was invited to present SMR jōdō at a March 1926 Tokyo Metropolitan Police enbu martial arts demonstration given in honor of comrades fallen in service. His demonstration, given with another Fukuoka martial artist, was an immediate sensation, and he was asked to move to Tokyo to teach SMR jōdō. Sometime later, he moved to Tokyo and began teaching SMR jōdō. Within a short time, he was teaching multiple groups from the Boy Scouts and soon to the Tokyo Metropolitan Police, (Morikawa T, 1961) one of the most influential martial arts bodies in Japan.

Shimizu caught the attention of Kanō shihan who hired him to teach at the Kodokan beginning 1931; Shimizu sensei mentions teaching “year to year” until the end of World War II, apparently meaning he was engaged as an outside, contracted instructor rather than joining the Kodokan staff like Heki sensei. (Morikawa T, 1961)

By the mid-1930s, for several years Kanō had explored the jō as an auxiliary weapon to fill the deficiencies of how jūdō can counter armed opponents. Beyond its practicality in exercise and self-defense, jō is also an excellent training in the judgement and use of maai, spacing between antagonists. In 1935, Kanō shihan introduced the new “Kodokan bōjutsu department” in Judo magazine.

Kagoshima native Heki sensei studied Kagoshima’s classic Jigen ryū Kenpō sword style as a child. He joined the Imperial Japanese Navy as an enlisted man and became a combat veteran, leaving the service in 1923. Kodokan managing director / jūdōka / former IJN Rear Admiral Honda Chikatami, who apparently knew Heki from his days in the Navy, recruited him into the administrative department. Heki graduated from the Kodokan’s elementary school jūdō instructor development training program, and somewhere along the way learned jōdō. (Honda C, 1944)

Leading by personal example, Kanō shihan was noted to be an early and enthusiastic practitioner of jōdō, but by 1935, the 75-year old’s chronic diabetes and subsequent circulation problems in his legs severely limited his mobility.

In March 1936, Kanō invited Count Henri de Baillet-Latour, the third International Olympic President and several other IOC members, in Japan to study Tokyo’s bid for the 1940 Games, to the Kodokan, where the demonstrations provided included bōjutsu. (Yokoyama K, 1943)

After Kanō’s death in May 1938, the Kodokan’s 1943 five-year memorial service featured a large group of Kodokan students and instructors demonstrating Kodokan bōjutsu.

Heki sensei died February 1944. During the Occupation and efforts to overturn the school budō ban, which put all public school jūdō instructors out of work, without fanfare Kodokan bōjutsu was abandoned.

Early in the Occupation police jō instruction was suspended as General Headquarters authorities directed the Japanese government to limit its use, as some of the GHQ staff, many of whom were civilian, liberal academics and lawyers before joining the war effort, were concerned about the injuries inflicted on some of the many leftist and rightist demonstrators and rioters in the postwar chaos by jō-wielding police. Despite that suspension, in 1949 the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Special Guard Force of around 300 fit, accomplished police martial artists trained by Shimizu sensei and armed with jō and keibō police batons was deployed against a large group demonstrating against the new Public Safety Ordnance that limited public assembly and protests. The Special Guard Force wielded their jō with particular enthusiasm that day, injuring many demonstrators and arresting 46.

GHQ responded by directing the Japanese government to outlaw the use of the jō completely, limiting the police to wield much shorter keibō police batons only. (Japan Wiki, keijo). But those soon proved unsuitable for controlling large crowds of rioters, some armed with cudgels and bats much longer than the police batons. Eventually the decision was made to allow the police to train correctly in more detailed and disciplined jō techniques, leading to the crowd control and measured, controlled strikes and thrusts shown in the video above. After better training, several reorganizations, and better integration with the police command and control, in 1957 a portion of the Police Reserves were redesignated as Kidōtai, Mobile Force units. Those highly trained, disciplined public safety force, organized as nine units based in Tokyo, Osaka, and other key cities, still occasionally carries the jō today along with more modern crowd control equipment. (Japan Wiki, Keishichoyobitai) But in reality, today the jō is more of a training device or symbol of authority hinting of potential violence more than used as mainstay riot control equipment.

Despite the Kodokan dropping jō training, Shimizu sensei went from strength to strength. He was soon busy teaching the postwar Tokyo Metropolitan Police and civilians all over Japan in the art of Shintō Musō ryū jōdō, now practiced around the world. After his death in 1978, jōdō splintered into several organizations as he never designated a successor or had a viable organization that could survive on its own.

One of the organizations that incorporated jōdō was the All-Japan Kendo Federation, the kendō counterpart to the new All Japan Judo Federation. The AJKF was established in 1952 in the vacuum left by the banishment and dissolution of the Dainihon Butokukai, the Greater Japan Martial Virtues Society, which had been the pre-Occupation, national level capstone martial arts and kendō organization, which used its broad base of kendō aficionados (perpetually some 4-5 times more numerous than jūdō players in Japan) to introduce the ancient art of the jō to new generations.

Kanō shihan had been proven right; like him, but decades later, one of Japan’s largest budō organizations in Japan also recognized the value of jōdō, absorbed it, and taught it throughout Japan, and later, the world.

Later in a separate essay we’ll disclose the ultimate plan of Kanō shihan – to absorb not only jō but also kendō into the Kodokan as subsidiary arts of jūdō, and how close he actually came.

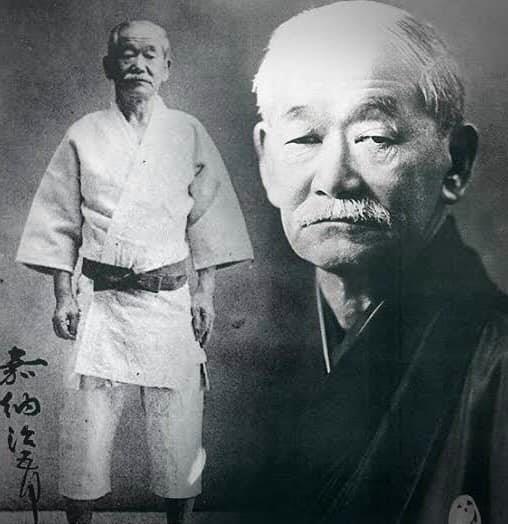

Jigoro Kano - We made bōjutsu training available to volunteers.

When I was young, I practiced Yagyū-ryū bōjutsu with a man named Oshima. As my practice of this discipline had not reached the level of shugyō (NOTE: in-depth study), usually I do not mention it. However, since then I thought there was value in bōjutsu shugyō. As I said previously, I am convinced that more research is desirable, namely that of jūjutsu (unarmed fighting techniques), bōjutsu (staff or stick techniques) and kenjutsu (swordtechniques).

Looking at the reality of our current society, when we talk about men, women, young or old, excluding the few people who actually have jobs that give the opportunity to carry a sword in his belt, no one carries weapons. Consequently, in the event of something unexpected, the martial art that is more useful is one that can be used to defend themselves without weapons. Considering things from this point of view, today the value of kenjutsu is relatively poor, but I am convinced that this, along with jūjutsu, has had for many years in our country a great value as a method of spiritual development. In addition to jūjitsu, we must consider the experience of bōjutsu, which is a very important thing that seems to be overlooked by manytoday.

About eight years ago (NOTE: circa 1927), we gathered volunteers in the Kodokan and started practicing bōjutsu with Tamai sensei, Shiina sensei, Ito sensei and Kuboki sensei of the Katori Shintō Ryū, all from Chiba Prefecture. About four years ago (NOTE: circa 1931) we received Shimizu Sensei of the Shintō Musō Ryū from Fukuoka and continue the practice of this technique. Today, thanks to Takeda sensei, Heki sensei, and with the help of others, we are increasingly able to practice these arts. In addition to beginners, we recently have about 50 participants, so many that we must practice in the main dōjō of the Kodokan.

In the future, in addition to the efforts made so far, we intend to continue to invite the great masters of bōjutsu. As we took the essence of various schools of jūjutsu to develop the basics of jūdō, we have had great success in gathering bōjutsu techniques from many schools and researching them. Now, we created Kōdōkan Bōjutsu as a branch of Kōdōkan Jūdō. I hope that we will be able to spread it throughout the world.

Although I said I put my energy in the development of bōjutsu, I still think that the unarmed martial arts have greater value. After that (basic understanding), I think, however, that the study recommended the (next most valuable) is the one where you learn to attack and defend using weapons. About weapons, I think it (NOTE: i.e., bōjutsu) is more important than the study of kenjutsu (sword arts) or that of the yari (spear) or naginata (halberd). People normally have easy access to implements such as sticks, walking sticks or umbrellas. It is usually easy to have at hand something like a stick or a piece of wood that, in case of emergency, can be used as an improvised weapon. In any case, bōjutsu is useful not only for the reasons described above, but also because it is suitable for routine practice.

Similarly, all bujutsu (fighting arts) require practice. As I say constantly about atemi jutsu (striking techniques with bare hands), used in Seiryoku Zen’yō Taiiku (“Best Use of Energy Physical Education”) that I developed and which uses atemi jutsu, consider the following. As you study atemi jutsu, it is very difficult to make the best use of this art in real world circumstances. Consequently, the great value of these techniques is that their practice can be used as a means of physical education.

It also important to consider that the techniques of striking and defending comprise a large part of the exercises, and practice from the beginning requires obtaining simple equipment (for example, just a jō and bare hands).

So recently I did some research regarding bōjutsu and decided to share it. I urge the start of the practice of this art as soon as possible for those who are interested throughout the entire country, region by region, under the guidance of instructors qualified to present the new branch of jūdō.

In developing the Kodokan and becoming capable in these practices, we will be successful and train instructors to be sent around the world. I think that in a few years, as jūdō is spreading throughout the world, there will come a time in which to spread bōjutsu abroad also.

Kano Jigorō, 1935

End notes:

EN1 – The jōdō instructor’s name in Japanese is 日置隆介. His family name can be read Heki or Hioki, but as is commonly the case, how it is properly read is not specified in scores of appearances of his name in Judo magazine. The author chose to use the pronunciation Heki to coincide with the Heki ryū martial archery school that uses the same kanji.

Bibliography –

Honda C, 1944, “Heki kun wo Tsuisosu”, in Judo, vol. 15, no. 4, Tokyo, Kodokan Bunka Kai. Kano J, 1935, “Kodokan ga Yushi ni Bojutsu wo Renshu Seshimuro ni Satta Riyu”, in Judo vol. 6, no. 4, Tokyo, Kodokan Bunka Kai.

Morikawa T, 1961, “Shintō Musō Ryū o Tazenete”,

in Sho Daimyō Hatamoto Okumuki Hisshi, special edition of

Kengō Retsudenshū No. 66, Tokyo, Futabasha, October 1961.

Members of the 5th Kidōtai Mobile Force, one of the five first established in 1957, training with modern riot gear against simulated rioters armed with jō

in a demonstration given before the 2019 G20 Summit in Osaka. Most of Japan’s Kidōtai along with a total of 32,000 Japanese police deployed to provide security for the event.

Source: Sankei News, 2019.

in a demonstration given before the 2019 G20 Summit in Osaka. Most of Japan’s Kidōtai along with a total of 32,000 Japanese police deployed to provide security for the event.

Source: Sankei News, 2019.